Many websites built by IT companies are stable, secure, and technically sound. But without an understanding of user journeys and behaviour, they often fail to generate real business results.

Taking over a website built by an IT company is a familiar scenario for us. The site mostly works. And yet, it fails at the one job a website actually has: getting people to do something.

This is not a criticism of IT companies. They are excellent at providing IT services. The problem is that websites are not IT systems. They are behavioural tools.

Many businesses don’t realise this. They see IT and web as being so similar, they’re practically the same thing. If an IT professional can set your laptop up for you, why couldn’t they create a website that you can view on the laptop? There are obviously a lot of crossover skills, but there are also a lot of skill gaps – accessibility, user experience, design etc.

IT expertise is not web expertise

IT companies are brilliant at:

- Email infrastructure

- Security and permissions

- Internal systems

- Software configuration

- Keeping things running reliably

But websites are not internal tools. They are outward-facing experiences. A good website requires understanding:

- How users arrive

- What they expect to see first

- What reassures them

- What confuses them

- What makes them hesitate

- What makes them click

Most IT-led websites are built from a technical perspective, not a human one.

The missing piece: understanding users

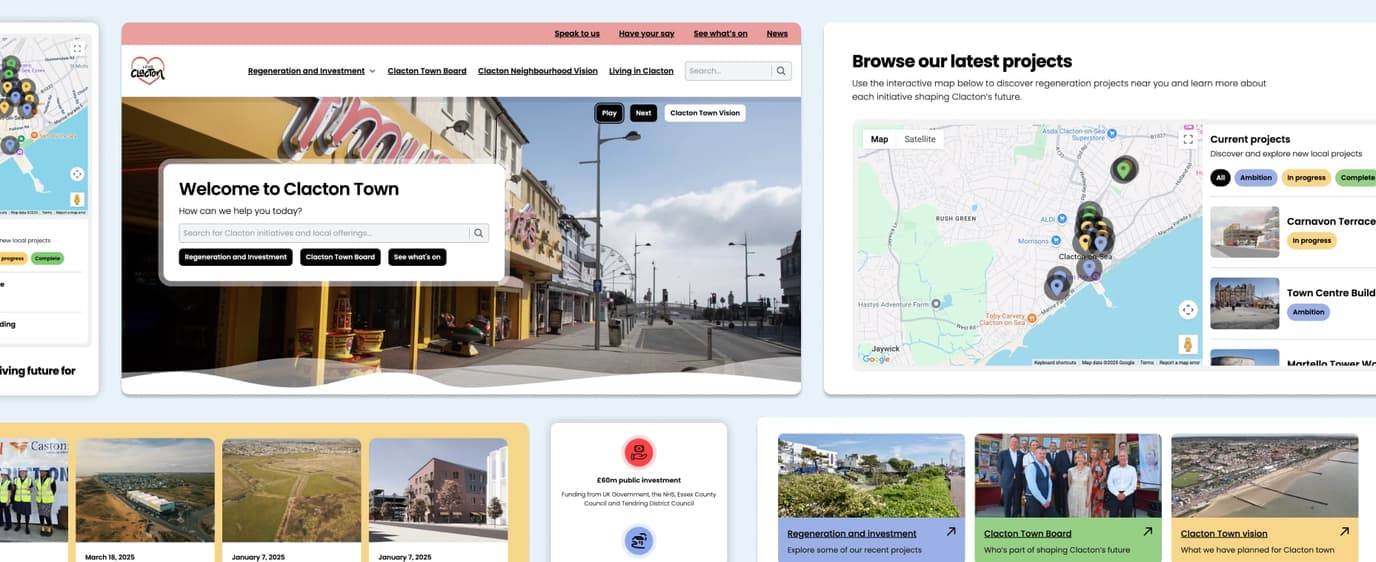

A user journey is not a theoretical concept or a UX buzzword. It is a practical way of understanding why someone has landed on your website in the first place, what problem they are trying to solve, what doubts or hesitations they are carrying with them, and what the most logical next step should be at that exact moment. Every page should be answering those questions implicitly, without the user having to think about it.

IT-built websites often assume users will simply work things out for themselves. Real users do not behave like that. If the next step is not obvious, they leave. If the content does not reassure them, they hesitate. If the layout does not guide their attention naturally, they scroll without direction or abandon the page entirely.

Design is about behaviour

Design is not simply about making things look attractive or tidy. It is about shaping behaviour. Good design subtly draws the eye towards key actions, creates a clear hierarchy so users know what matters most, and uses spacing and layout to reduce the mental effort required to understand what is going on. It makes decisions feel easy rather than forced and builds trust without the user consciously noticing it happening.

IT-led design tends to focus on alignment, consistency, and fitting content neatly into a predefined structure or template. While those things are not wrong, they do very little to encourage action on their own. A “Contact us” button placed arbitrarily on a page is not a call to action, just as a dense wall of text is not clarity. Even a layout that is technically correct and logically structured can still be deeply unusable if it does not account for how people actually read, scan, and decide.

Common problems

When we take over websites originally built by IT companies, the same patterns appear again and again. Pages often lack a clear primary goal, with multiple competing calls to action that dilute rather than reinforce intent. Navigation is frequently structured around internal departments or services rather than the way users think or search. Content is written to satisfy internal stakeholders, not to answer customer questions, and forms tend to ask for too much information too early on, and overwhelm. On top of that, there is often little genuine consideration of mobile-first behaviour, despite the majority of users arriving on smaller screens.

None of these are technical problems. They are experience problems, and they sit squarely in the gap between “the site works” and “the site performs”.

The cost of getting it wrong

A poorly designed website often doesn’t fail in an obvious way. Enquiry volumes drop, or never reach their potential. Lead quality suffers. Sales cycles become longer and more labour-intensive. Users resort to emailing or calling because the website does not guide them effectively, and teams start blaming a lack of traffic when the real issue is friction.

On the surface, the site looks ok. Underneath, the metrics tell a very different story.

The right collaboration model

This post is not an argument for one discipline being more important than another. It is an argument for clear roles and collaboration. The strongest websites are built when IT teams support on hardware and systems, while web specialists focus on user experience, content, and conversion. When design decisions are driven by how people behave rather than how things should theoretically work, the results are measurably better.

When one discipline tries to cover all of it, something important is almost always missed.

This is why whenever we have clients ask us for IT support, we always recommend them to an IT company we trust.

In summary

If your website was built by the same company that manages your email servers, it is worth asking a couple of simple questions. Did they ever ask what you want a visitor to do within the first five seconds of landing on the site? Did they design the experience around that goal, or did they simply apply a template and make it fit?

If the answer to those is no, the website may be working fine from a technical point of view, but it is unlikely to be working commercially. And that is usually why we are asked to step in and redesign websites originally built by IT companies.